It’s the day of my 26th birthday—March 12th, 2020—and the pandemic is tipping over the precipice, the toilet paper is still starting to fly off the shelves, and it’s just about time for a drink. I get a phone call from one of my friends.

“I’m thinking of driving out to the Kroger in the suburbs,” he says. He’s forgotten it’s my birthday, which is just fine with me. “They’ve got a bar, and I wanna watch rich people do all the shit they say poor people do.” He inevitably scoops me up in his Cherry Red Kia Soul, and we Google the Kroger bar to find out its phone number, calling ahead to make sure it hasn’t already been turned into ruins.

“Krobar,” the bartender answers.

We’re pushing our carts around with draft beers in the cupholders not long after. The scene is so chaotic, the air so tense, you feel like dropping a match could send a ball of flames into the world. “I might get some spaghetti,” I say. My friend and I each grab some boxes of dried noodles, and then I put one or two back in its place. “I’ll be fine.” We’re both bartenders, and the money hasn’t been great lately.

Neither one of us has a clue just how much of this will be gone soon—how much of our lives will be lived inside our homes, how many of our meals will be eaten out of boxes, how much of our exceedingly social jobs will have to be re-imagined inside this new container called Novel Coronavirus-19.

If we had, I might have had another beer.

Alone in my house, nearly a full year later, I pull a box of Hamburger Helper from my pantry. I notice that I can see the back wall of the cupboard in the space it leaves behind.

I’m reaching the last of my reserves.

“I get so sad when my food’s coming to an end,” Kevin James says in an early episode of The King of Queens. He’s eating a Snack Pack on the couch. Leah Remini sits beside him wrapped in an afghan. A TV drones on in the background, a TV on the TV. “You start seeing the bottom of the container, and you know it’s almost over.” The studio audience laughs—a portrait of civilized life. A portrait of American life, anyway—a life surrounded by little deaths, things that wear out, the objects of mass production. It’s a portrait of a life in which “man is brought home to himself by an irresistible force,” as Alexis de Tocqueville puts it—we don’t deny the bottom of the container, but we do try to hide it somewhere else. Dying is a hot potato. As it does with so much else, Democracy in America predicts that we will open another Snack Pack. It also tells us that that Snack Pack will have a bottom, too.

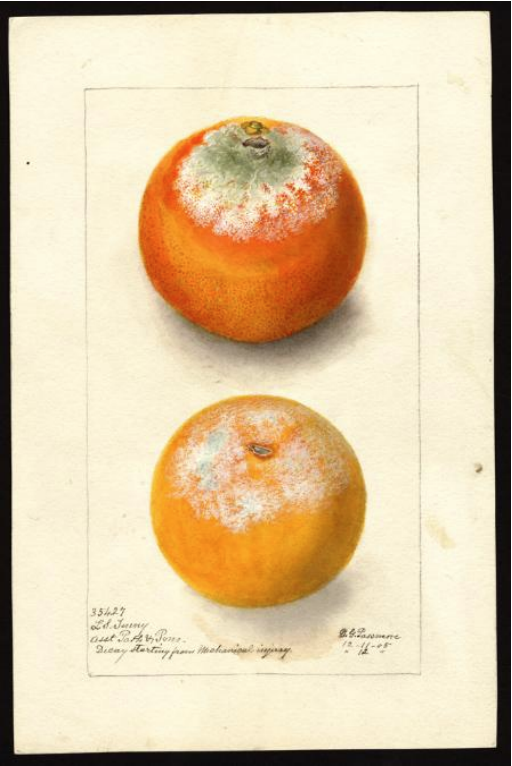

In 1886, the US government commissioned a series of 7,500 watercolor paintings of every known fruit in the world. Called the Pomological Watercolor Collection, about 65 American artists contributed to this vibrant, colorful, and incredibly detailed body of work, which even today feels much more significant than it does ornamental. But none of that began until about 70 years after the introduction of ‘pomology’ into the world, a word that means—now, as it did then—the science of growing fruit. As the United States’ farmers and government worked together to set up the orchards which would facilitate its emerging fruit markets, they needed a term to identify exactly what it was they were doing. Farmers who engaged in pomology had to be able to talk about it—both with one another, so that they could trade industry secrets, and with the government, so that they could report back on progress. Both ways of talking about it meant making more money. But whether it was you or someone else who was using the word, what gave ‘pomology’ its meaning was the context in which it was being used.

“Do you know what a mart is?” Milo Minderbinder, the impossible mess officer, asks the main character Yossarian in Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.

“It’s a place where you buy things, isn’t it?”

“And sell things,” corrected Milo.

“And sell things.”

“All my life I’ve wanted a mart. You can do lots of things if you’ve got a mart. But you’ve got to have a mart.”

Heller describes Milo as having an “unfortunate” mustache, and “disunited eyes”, which never settle on any one thing at a time. “Milo could see more things that most people, but he could see none of them too distinctly.” Early on in the book, Milo gets a letter ordering him to spare no expense, to give Yossarian as much of the mess hall’s fruit as he asks for, because Yossarian has a liver condition keeping him out of combat. Yossarian’s liver condition is that he doesn’t have a liver condition. But it looks a whole lot like he does, and that’s the only thing keeping him out of combat. It’s a condition that “isn’t easy to come by,” he explains, “and that’s why I never eat any fruit.” It turns out that Yossarian’s just been giving it all to his buddies.

Milo doesn’t understand:

“I have to give you as much as you ask for. Why, the letter doesn’t even say you have to eat all of it yourself.”

“And it’s a good thing it doesn’t,” Yossarian told him, “because I never eat any of it.”

At first confused, and then horrified, Milo quickly decides that he should be relieved instead. After all, it means Yossarian is the most trustworthy person he knows—“anyone who would not steal from the country he loved would not steal from anybody.” Since it’s been authorized by Doc Daneeka, Milo reasons, Yossarian’s not technically stealing the mess hall’s fruit. And once it’s Yossarian’s fruit, he can do whatever he likes with it, even if that means giving it away to be sold on the black market. Milo realizes that he could use a few favors himself, and it’s not long before he’s in Germany, fighting on both sides of the second World War.

Just like ‘pomology’ offered a language for organizing fruit-growing ideas into a widely-recognized science, the watercolors of the Pomological Watercolor Collection visually represented the mastery we felt we’d developed over the fruit that grew all around us. That we could recreate it meant we’d seen it, had it, experienced it. Through their constellation of beautiful shapes and colors, the watercolors showed us how the fruit looked, how it could be taken apart, how it would decompose. But by also converting an encyclopedic amount of information into the visual format of writing, and then integrating that writing into a painting, the watercolors sought to bridge the gap between ideas—the things inside the mind—and objects—the things inside the world. The Collection was an anxious attempt to capture, in a single moment, the very existence of every fruit being grown, purveyed, bought or sold at any one time. It was trying to get a look at the real picture, to take inventory of the things we put inside ourselves.

Eating can be a gateway drug. Having eaten is to have aligned things in both worlds, the internal world and the external one. Everything is to be economized in a way that’s considered satisfactory. If we’re “peckish”, we “snack”; if we’re “starving”, we “feast”; if it’s a holiday, we gorge ourselves. In any case, we’re told that context is required about the eating, a standard must be referenced, excuses must be made. Eating develops connections that didn’t exist before between things, moments, ingredients that certainly did. A permanent transformation occurs. But we’re never satisfied with the fullness of yesterday’s meal once we’re hungry again.

The American manner of eating in this way is akin to the colonizer’s need to recontextualize everything within themselves. This tendency is crystallized in the poetry of William Carlos Williams, in whose “imagination” all kinds of oddities live, co-exist, are penetrated with one another—the imagination is where ideas cut other ideas like a knife. “Having eaten to the full, we must acknowledge our insufficiency since we have not annihilated all food,” he says in Spring and All, which I’m reading at a bar. “However we have annihilated all eating : quite plainly we have no appetite.”

“What do you think?” an older guy beside me asks. He gestures toward the book. I’m new here, but somehow I can tell he’s a regular.

“I like it so far,” I say. He nods.

“It’s a handful. A slow meal. But you’ll be glad you read it.” I’ll never forget that. It’s the imagination that saves us from the banality of bursting ourselves, Williams says. I’ll go on to become a regular at this bar—a container—by the end of 2020—another container.

Back in the present, I rummage through the freezer, producing a Ziploc container of ground turkey for the Hamburger Helper I’ve pulled from my pantry. I bought an oversized package of turkey sometime in the last year for $1.99 a pound. I don’t know when it was, but I remember seeing the price on a sign. If only I’d looked at a calendar while I was at it.

“You were right about the sales on meat,” I text my father.

“You can freeze bread, English muffins, and tortillas,” he texts back. He gives me a call.

“I’ve been eating a lot of Hamburger Helper,” I tell him over the phone. We’re having a beer together.

“You can buy the Kroger brand for a third of the price,” he says. “The kids don’t even notice the difference. We tested.” My father is talking about my brother, who’s ten years younger than me, and my sister, who’s two years younger than him. He’s not talking about me, from the other marriage, who—somehow, overnight—isn’t a kid anymore. I can feel beers in the morning.

When we hang up, I start to make the food I’ve been talking about for the last hour. I look at the anthropomorphized, bleach-white glove on the bright red box—the “Helping Hand”, as he was originally called, or “Lefty” as he was eventually christened. I recognize him as a sign of my childhood, somehow still here after all these years. Lefty’s lived longer than some of my friends.

Suddenly I’m considering the weight of my memory. He’s been here all along. Was I thinking about Lefty? Was I thinking about my father? Both had managed to endure somehow, despite all odds. In my early 20s, my father’s declining health was often a topic of concern. In the early 2000s, Hamburger Helper implemented quick decisions to stay ahead of a market on trucker speed. In both cases, the terms of life were renegotiated by exploiting the sign of an animal product—my father went to the Mayo Clinic, Hamburger Helper dropped the word ‘Hamburger’ from its name. But both have exactly the same flaw: neither man nor beast can stop the inevitable.

“SPEED IS NOT THE NEW NORMAL,” a digital sign screams over a Tennessee state highway. I can no longer be convinced. It’s all speeding up. Now that I’ve arrived in the second quarter-century of my life, my thoughts turn increasingly to the last one, yet I somehow keep generating the next. Karl Ove Knausgaard tells me in a book from 2009 that I’m able to understand everything because I’ve turned it into myself—I can recognize it as instantly as I can my own reflection. “The whole of the physical world,” he says in My Struggle: Book One, “has been incorporated into the immense imaginary realm.” And he’s right: existence has closed in on itself. Because of virtuality—that reality which the ‘real’ world defines by rejecting itself—I can close my eyes and conjure up the faces of people who I’ve never met, who I’ve seen on-screen—which means I can also dream infinite faces when I close my eyes in the other direction. When I think about the face of Lefty, he appears out of nowhere, my memory serving as his only medium.

The peculiar thing about Lefty’s eternality is that it was developed in a marketing room. After deconstructing their relationship with the world, if people wanted to keep selling their food, they had to deconstruct their relationship with their own bodies. People made the decision to separate the left hand from the cooking process—a process which people also invented—and then gave it back its identity, now marked forever by its status as an icon. Lefty was one of the first celebrity chefs. But unlike my left hand, which plays an instrumental role in my cooking, Lefty only ever serves, can never be served. Lefty himself never eats Hamburger Helper. And also unlike a hand, Lefty has two eyes just like I do, peering at me here inside my kitchen just like my father used to. A human hand can’t do that. But this isn’t a human hand, it’s Lefty, and he really does have eyes—can you imagine him without them? I seem to have inherited him from my father and stashed him away in my cupboard, just like the parts of myself I’d rather forget. Am I what I eat yet? Have I been brought home to myself?

“Dad wants to know why this was in the laundry room closet,” says Denise, a character in the Jonathan Franzen novel The Corrections, confronting her mother about a check made out to her rapidly deteriorating father. Denise rifles through the closet in the basement, tossing out the “Neolithic cans of hearts of palm and baby shrimps,” “the turbid black liter of Romanian wine whose cork had rotted”. Denise tears out the “quart glass bottle of Vess Diet Cola that had turned the color of plasma” and the “jar of brandied kumquats that was now a fantasia of rock candy and amorphous brown gunk.” Denise extracts every object as though it were an infection from a gaping wound. But each one is wholly recognizable in the text, existing for us as a hyper-specific image which we conjure up at or against our will. Like Denise, we know our food. Denise just knows it a little better—she’s the former manager of a New American restaurant in Manhattan. But as she tries to reassemble one of her esteemed dishes on her mother’s home-grade Kenmore, she remembers suddenly that food is never quite what you think it is. “You forgot how much restaurant there was in restaurant food,” Franzen tells us that she’s thinking, “and how much home there was in homemade.”

On August 4th, 2020, mass media did it again. This time it was a show called What’s it Worth? Hosted by Jeff Foxworthy—himself a relic of a celebrity class now suspended in time, as though “uploaded” into the oughts—the show was about the secret treasures that lurk within our homes, how much we could sell them for if we had to. It was a painkiller for a depleted American audience. On September 1st, the ninth episode of What’s It Worth? featured the original Lefty muppet from the Hamburger Helper commercials of the 70s and 80s. It was shown from inside the home of the Amazing Azens, who were also shown inside of it. It was the moment the Azens had been waiting for: they were seen on national television, watching Lefty’s authenticity get verified, then watching Lefty get appraised by a professional auctioneer. Whether or not they cashed in, the Amazing Azens had let everyone know that they’d put a price on the Helping Hand. The ephemeral quality of the knick-knack was made concrete in a pop media spectacle—and Jeff Foxworthy was the one showing it to us. If you’re lucky, you might be a redneck, even after all these years.

“Sadder than destitution, sadder than a beggar is the man who eats alone in public,” says Jean Baudrillard in America, his book about America, “for animals always do each other the honor of sharing or disputing each other’s food.” Keith Ferrazzi, on the other hand, author of Never Eat Alone, tells us to “[i]dentify the people in your industries who always seem to be out in front,” and then to “[t]ake them to lunch. Read their newsletters. In fact, read everything you can.” In both cases, for very different reasons, we’re told that we must eat in order to belong. It’s a matter of consuming ourselves in our food, in our information, in our work. Meanwhile, I brown the turkey.

In 1979, veterans of camp Sam Raimi and Bruce Campbell created a short film called “Attack of the Helping Hand”. The scene is simple: a young woman, alone in a dark home, pulls a box of Hamburger Helper from her cupboard. In the short film, just like on TV, Lefty appears.

“Hi! I’m Hamburger Helper’s Helping Hand, here to help you out with your meal!”

“You’re cute!” laughs one young, patient, Linda Quiroz. Suddenly, she’s defending herself from the left-hand glove clutching at her pearls. She tries drowning him in the sink, and when that doesn’t work, she leaves the kitchen instead.

A gloved left hand grabs her by the shoulder in a pitch-black corridor—but as she twirls around, throwing a human body to the floor, we see that it’s only the Milkman.

“Jesus Murphy, lady!” the Milkman cries. “You must have rocks in your gourd or some damn thing!”

Despite the fact that no explicit rationale is presented, we’re led to believe that this is the home of an unseen nuclear family. Lefty certainly represents an intrusion of that home, as he assaults the woman in the kitchen of the very lifestyle he advertises. Representing the second intrusion, however, is the Milkman from decades before, who somehow still seems to have more in common with the woman than Lefty does.

The woman breathes a deep sigh of relief. The Milkman is only human, after all. Maybe he can take care of that terrible thing lurking around the corner. But just a moment ago, it didn’t matter who he was—the Milkman was as unwelcome as Lefty in the inner dwelling of her home. The Milkman even has the nerve to tell her, “You scared the bejeezus out of me!”

Among other things, this short horror signals a deep and domineering change in the way that brands were taking hold of American lives in the late 70s. By then, the Milkman was dead—but the Milkman was only the beginning. When the young woman finally throws Lefty through a food processor, the Pillsbury DoughBoy springs to life right in his place. These things are inside the home now, they’re connected to the things we put inside our bodies, and it feels too late to escape.

I pull the empty box of Hamburger Helper from the trash can so that I can read the instructions on the back:

BROWN. Brown beef in 10-inch skillet over medium-high heat 6-7 minutes, breaking up and stirring. Drain; return cooked beef to skillet.

STIR. Stir in hot water, milk, Sauce Mix and Pasta. Heat to boiling.

SIMMER. Reduce heat. Cover; simmer about 12 minutes, stirring occasionally, until pasta is tender. If necessary, uncover and cook, while stirring, an additional 1 to 3 minutes to desired consistency.

ADD YOUR OWN TWIST! Add some zip and zest; stir in chopped dill pickles and shredded Cheddar cheese just before serving. Serve with hot sauce.

I was enamored by the idea of adding in Cheddar cheese, and the dill pickles were a kind of alluring oddity. But I didn’t have either of those onhand. Should I drive back to the store? Should Hamburger Helper cost as much as a meal made from scratch?

“People face trade-offs,” Greg Mankiew lists as the first principle of economics in Principles of Economics. Greg Mankiew was the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush. Some edition of Principles of Economics is perhaps the most seminal text in the American undergraduate Economics 101 classroom. The original edition was published in 1997, and it can still be found for one-third of the price of the newest edition on the internet. Even cheaper still is Principles of Economics, another book altogether, written by a man named Alfred Marshall in 1890.

17 years after the publication of Marshall’s own economic principles, Henry Adams recalls that, as he had understood it up until now, science itself meant the “economy

of

forces.” On the other hand, standing in sheer awe at the combating forces of the World’s Fair in 1900, Adams “

knew

neither

the

formula

nor

the

forces.” Where the eager drive toward scientific understanding had seemed to root out the very question of the unknown, it had also made the understanding itself impenetrable—every discernable quality of the human experience had already been raised to the level of the understanding. Now people did science experiments on science experiments, created energy out of energy. What happened when you stopped being able to tell what identified this thing from that one? What did you eat when you couldn’t sink your teeth into anything? Did you become Yossarian, who couldn’t eat fruit, or did you turn into Milo, who couldn’t eat fruit?

In the middle of the twentieth century, home brands like Ball Jars published pocket-sized recipe pamphlets which encouraged consumers to buy their products. The brightly illustrated pamphlets came packed full of tips and opportunities to economize the home, which would, in turn, economize the country. “Can More in ‘44!” reads one slogan. The publications created a vast mythos of gelatin salads, floating islands, jelly braids, hotdishes, bar desserts. One Canadian pamphlet from 1952 called “Family Meals” tells their reader, “You want your children, your husband, and yourself to eat all the foods needed for good health. You must keep within your budget as well. All this takes skill and careful planning.”

Much like the Adams story, in the recipe pamphlets, there was an implied sense that natural forces could be balanced, as well as a deep anxiety over finding that balance. Also like in the Adams, the individual needed a translator if they wanted to tap into it. Henry Adams had Samuel Langley. The homemaker, in turn, had the home economist. But whereas the distance between Adams and Langley had been the space between their bodies, the distance between the home economist and the homemakers was exactly that of a publication. This allowed the home economist to be fictionalized, as in the case of Edith Adams, so that the person telling us about our homes, and by extension about ourselves, was actually a rotating cast of multiple people, a myriad of personalities represented as one single image. If the homemaker was going to be just like Edith Adams, they had some big shoes to fill.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the pamphlets, there was the same degree of madness. There were company test kitchens, inside of which there were home economists. And inside the home economists was the immutable drive to put their foodstuffs inside the family home, no longer fragmented by a World War. One day in 1955, inside of a Campbell Soup Company test kitchen, Dorcas Reilly invented the green bean casserole. Formally stylized as Green Bean Casserole, it had come to Reilly suddenly, as though from the heavens above, after countless experiments.

Green Bean Casserole contained just three main ingredients: green beans, fried onions, and Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom Soup. Invented in 1939, Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom Soup had colloquially taken on the nickname of “Lutheran binder”. It provided the specific agency that congealed church dinner casseroles, which in turn binded countless Midwestern bodies together in fellowship within church walls. Not once in recorded history had it occurred to anyone to invite frozen green beans to the party—until one day, when it finally occurred to Dorcas Reilly. In a 2005 interview with the Alternative Press, exactly one half-century later, Dorcas Reilly famously said that she didn’t remember doing that. “Frozen air...had some scale of measurement, no doubt, if somebody could invent a thermometer adequate to the purpose,” Henry Adams says as he grasps for the index of his own soul. “[B]ut X-rays had played no part whatever in a man’s consciousness, and the atom itself had figured only as a fiction of thought.” It seemed conceptually required that an atom couldn’t be inside the imagination, and yet, somehow, we seemed to have proof that it had been there before. Henry Adams stood in puzzlement at the World’s Fair, his “historical neck broken by the sudden irruption of forces totally new.”

When I dump the Hamburger Helper into four separate bowls, a little bit splashes on the stovetop. I’ll clean that up tomorrow. As for tonight, I’m “meal-prepping”—rationing out exact quantities of the food I’ve prepared in order to satisfy my budget, schedule, and dietary requirements. Three of these bowls will live covered up in the fridge, unless I decide to eat seconds. Seconds, reciprocity, duplicity: I made two Green Bean Casseroles in 2020. One was for Thanksgiving, and one was for Christmas. Both times, I was quarantining away from my family. Both times, I used the recipe on a jug of French’s fried onions instead of a can of Campbell’s soup. And both times, I celebrated with a friend who’d contracted COVID-19 right around the same time as I did. Since his job went remote last March instead of disappearing like mine, the two of us have just endured very different years. But somehow we’ve been preserved, and here we are, awaiting the bottom of another container.

originally published in the spring 2021 issue of This Wonderful World Magazine.